Article

An integrated psychiatric care campus

Gideon Boie

2013, Psyche

In 2006, PZ Sint-Norbertus psychiatric hospital, part of Emmaüs npo, compiled a spatial master-plan for the campus on its own initiative – a document drawn up by the engineer-architects Marc Hendrickx and Ramon Kenis. This document defines the opportunities for spatial development on the campus, both in terms of internal organisation and integration into the immediate surroundings. This set out the guidelines for the upgrading of its grounds. Now, with the master-plan, the institution is able to gear its building specifications to the existing spatial qualities (lakes, green zones, driveway, etc.) and other factors in the surroundings (village centre, station, access road, etc.)

This master-plan gives PZ Sint-Norbertus a unique position in the care landscape in Flanders and in psychiatry in particular. Even though the master-plan is modest in its ambitions, it is nevertheless a pioneering document in a sector that has a considerable effect on the environment we live in. The Sint-Norbertus campus occupies a large area of Duffel that is bounded by Spoorwegstraat, Stationsstraat and Rooienberg and stretches from the station to the church. Furthermore, programmes that involve a great deal of urban activity are concentrated on the psychiatric hospital site. This complexity is now for the first time being analysed and structured on the basis of a spatial master-plan.

Luc Pelgrims, the Technical Director at PZ Sint-Norbertus, describes the document as a ‘backbone’ that can be referred to in decision-making processes. It enables the institution to include the work of the whole campus when decisions have to be made about individual building plans. The present spatial quality of the campus, sometimes rather shameful, is after all not so much the consequence of the primacy of care strategy considerations in the design (which could be justified); the problem is, rather, that the decision-making process is oriented entirely towards care needs. In no way was the spatial location of the care project taken into account. This meant that the spatial quality was invariably compromised by urgent needs and chance circumstances.

On top of this, the contract allocation procedure has not been at all transparent for architects, even though it is precisely their initiatives that were so important in the achievement of spatial quality. By means of the master-plan, the hospital’s technical department enhanced its share in the spatial quality of the individual building projects. The master-plan is an instrument by which to establish a previously nonexistent discourse on the experiential and visual value of the campus in relation to the overall vision of the normalisation of psychiatric care.

The master-plan analyses and structures the spatial organisation of this psychiatric institution so that it does the greatest justice to the vision of care. We can summarise it in two major elements.

In the first place, PZ Sint-Norbertus arose out of a former monastery site. The psychiatric institution was accessible only via the monastery – a wall, literally as high as several houses, which isolated the institution from its urban surroundings. This also meant that the institution grew out of the monastery, which can be seen in the dense building in the monastery’s back garden. The monastery’s regulatory function has now been taken over by the reception and administrative building in Stationsstraat. This introduced a new circulation pattern that is at odds with the historical buildings and, moreover, was never logically geared to buildings added later.

Secondly, in the course of time PZ Sint-Norbertus has developed into a hospital environment for psychiatric treatment. The clinical function ultimately also determined the auxiliary programmes that are now housed on the campus, such as the general hospital with its nursing school, the housing for the elderly and the municipal museum of nursing and local history (in the old mansion). The secondary school is the exception to this. The programme of the hospital also resulted in a typology where each building has a single central front door serving 150 beds. This mono-functional and also collective approach to psychiatric care no longer matches current concepts. These days, PZ Sint-Norbertus aims for short admissions to the institution coupled with long-term care outside it. This care is provided in Psychiatric Care Homes and sheltered accommodation in the proximity of the campus.

So the spatial master-plan breaks down the isolation of PZ Sint-Norbertus in Duffel and puts it on the map as a fully-engaged part of the town. To this end the master-plan defines two axes (N-S and E-W) that ensure a connection with the surroundings and make the site easily traversable for everyone. These axes draw the life of the town into the campus in several ways, for example by providing a short cut for cyclists, a place to hang around for youngsters, a park for walkers and for visitors who come specifically for the art. In this way the campus becomes much more of an integrated environment for living – though it is closed to traffic at night – instead of a desolate care campus that alienates its users from ordinary life. A well-considered spatial order thereby forms the key to an inverse socialisation of mental health care.

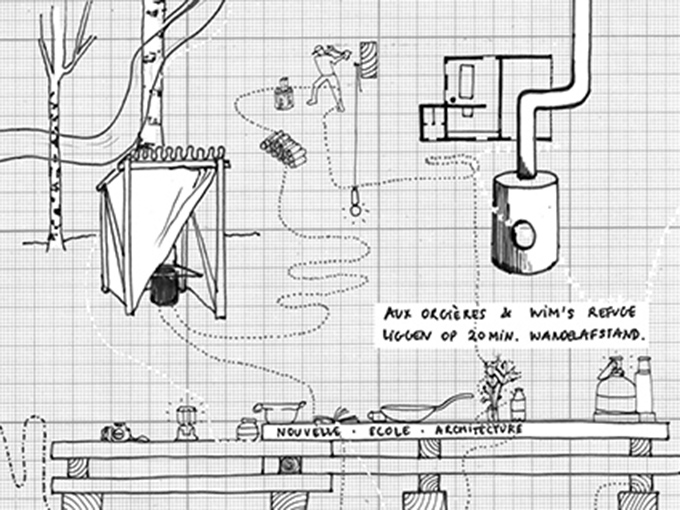

An additional way of developing a valuable environment for living is the choice of a new spatial housing model based on the archetype of the Flemish house: the detached house in a rural area. In this model, a maximum of ten patients live together in a home with individual rooms and communal front and back gardens, while the traditional back extensions (garages, garden sheds and workshops) are newly conceived as a therapy room. This choice clearly breaks with the traditional collective amenities in favour of an almost family-like housing situation.

This simulates a more normal residential setting where there is a clear and immediate boundary between the private home and the communal space. This also means that the therapy area is outside the home – except for the closed wards – and patients are thereby prompted to engage in mutual social intercourse. With these principles of spatial organisation, PZ Sint-Norbertus thus also follows its own socio-therapeutic model. The cohabitation of the patients is seen as a full part of the therapy. For the same reason PZ Sint-Norbertus prefers not to provide different types of housing related to different disorders.

In combination with the exceptional works of art created on the campus, its well-considered spatial order contributes to its experiential value for its users. At least as important is also the contribution this all makes to the general image of mental health care in society.

Published in Psyche 23 (4), December 2011, quarterly magazine of VVGG

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article