Article

The garden, the kitchen table and the artist

Gideon Boie

09/2018, Psyche

‘Don’t Eat The Microphone’ is a modest yet remarkable and engaging art installation in the backyard of the Dr. Guislain Psychiatric Centre (Ghent). The artwork set up by Veridiana Zurita, Petra Van Dyck, Lea Dietschmann and Stan Antheunis merges the parallel universes of psychiatry and culture. The work also shows how cure rests on a mutual relationship.

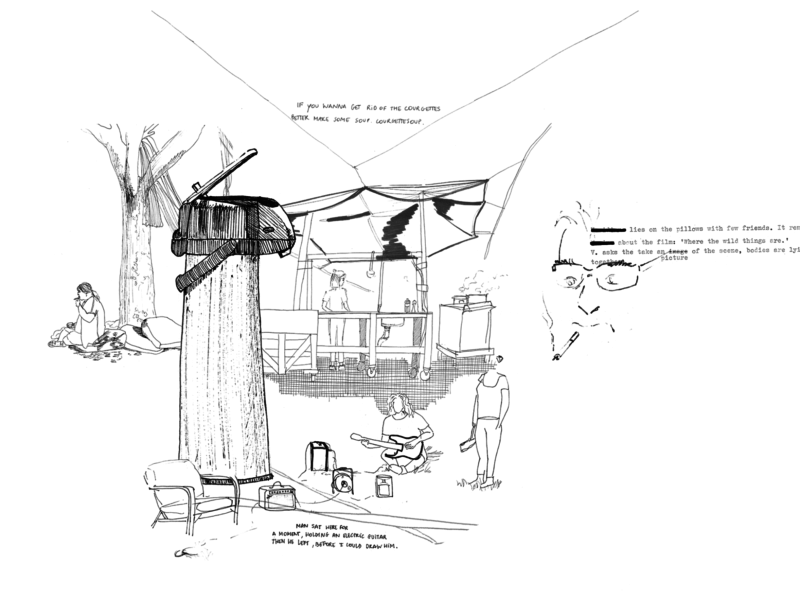

Don’t Eat The Microphone is an unpretentious installation in the backyard of the Dr. Guislain Psychiatric Clinic. A few pieces of furniture are spread around a big tree, in the shadow of the water tower. Curtains are hanging from the trees and plastic sails weave in the wind. A few persons are loitering, the one is busier than the other. Microphones are spread around, creating a soundscape that mixes music, casual talks and accidental noises.

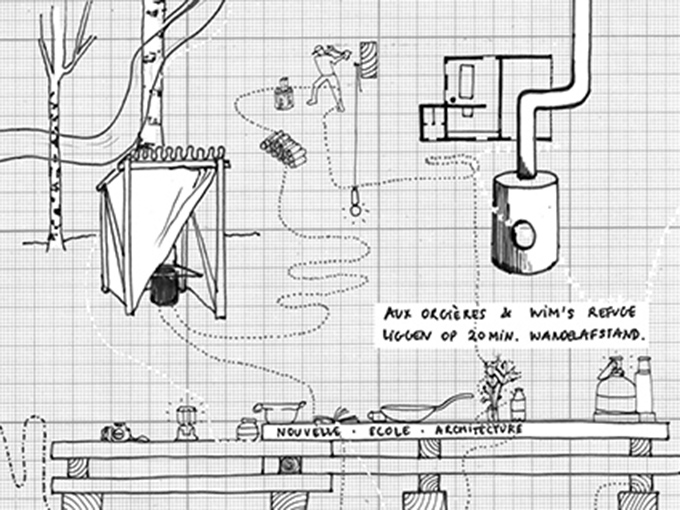

The art installation is a sort of anti-pavilion, taking place for one month and expanding steadily. A cabinet-maker constructs a mobile kitchen, a long kitchen table, benches, salon table, worktable, rocking chair, etc. A coat hanger, beanbags, plastic green house, typewriters and sound system are set randomly. The furniture and props seem to find a place according to the changing weather conditions.

Most importantly the artists are present all day, from 9:00 to 18:00, the whole month, as if they mimic the working day at the hospital. Every morning the pieces are put in the garden. They turn the buttons at the sounds system, they welcome the guests, they lay down on the ground, they loiter, they cook the lunch, do the dishes, whistle in the microphone, gather blown away pieces, chit chat here and there, and so on. At the end of the day they tidy up and clear the place.

The psychiatric context makes the art work peculiar. It is a constant coming and going at Don’t Eat The Microphone. Everybody is busy doing whatever. The one drops by to make some jokes, the other to light a cigarette. Still another reads out loud a poem or starts a discussion on the notion of happiness. Meanwhile, someone hangs around the kitchen and snoops in the pots. People do what they always do. There is always a good reason to disappear from the scene and equally good reason to reappear a little later.

Remarkably, the setting subverts the traditional hierarchies between care-givers and care-takers. At Don’t Eat The Microphone the patients become indistinguishable from staff or artists. Suddenly the good-natured young lady appears to be patient at the clinic, feeling overwhelmed by so many emotions at the same time. Still, she cooks a fresh pesto pasta for the group while animating some lost visitors. A guy talks about his work with psychiatric youth. Later it becomes clear he himself is recovering from a psychotic break.

In the same way, the idea to consume art is put upside down. At a certain moment, a group of visitors arrive at Don’t Eat The Microphone. They are in a state of confusion, since nobody could help them when they arrived at the hospital, not the general receptionist, not the museum guards, not even the passers-by. Signposts would certainly be of help, the visitors said. In a talk with a patient, their expectation in art is given a next blow. The visitors disappear quickly, with good reason, as they came to Ghent to do some shopping also.

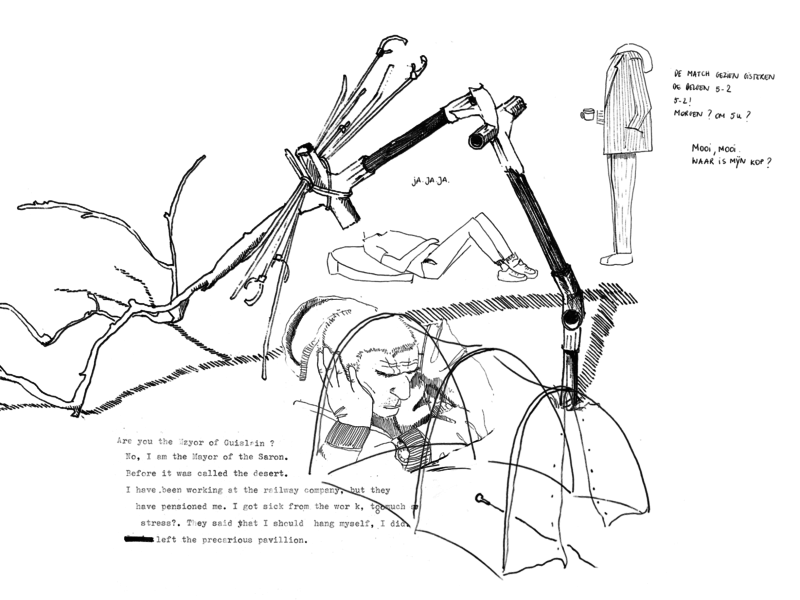

The element of surplus time is an essential element in Don’t Eat The Microphone. The full-day presence, over one month long, enables the artists to build up trust and trigger engagement with the people at the Psychiatric Clinic. There is not the slightest pressure to participate. For one person, the permanent presence may be crucial in appreciating the setting as part of the familiar activities in the psychiatric centre. For someone else, having a bad day, the permanence may provide the certainty that tomorrow is another day.

The art project articulates another place within the psychiatric centre. At the end of the day a young man hangs in the relax chair. As I weave goodbye, he gets up and expresses his admiration for the setting in the garden. He suffers from negative thoughts, but experiences the atmosphere in the clinic – with its medicines, injections and the bare corridor walls – as fuel to the fire. It is like healing negativity with negativity, he says. The garden became a refuge for him, making him say that the overgrown grass fostered his recovery certainly.

Who could have dreamt that a stay at the psychiatric centre could become something to cherish? On the final day, end of June, people show up to say farewell. The atmosphere is melancholic as people anticipate the lack they will experience from tomorrow onwards, as the garden will be empty again. Suddenly people start to divide the contents of the art installation. Someone says he will take one of the benches to his new refuge place in France. The kitchen will move to the local bio market. An elderly lady is given the vinyl with her favourite music from Vangelis, making her say that she wants to eat the artist.

Draft translation of a text (original in Dutch) published in Psyche 30 (3)

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Art

Type: Article