Article

Design Dialogue and Co-Autorship: a Social-Constructionist Approach

Herman Roose

2019, VAi

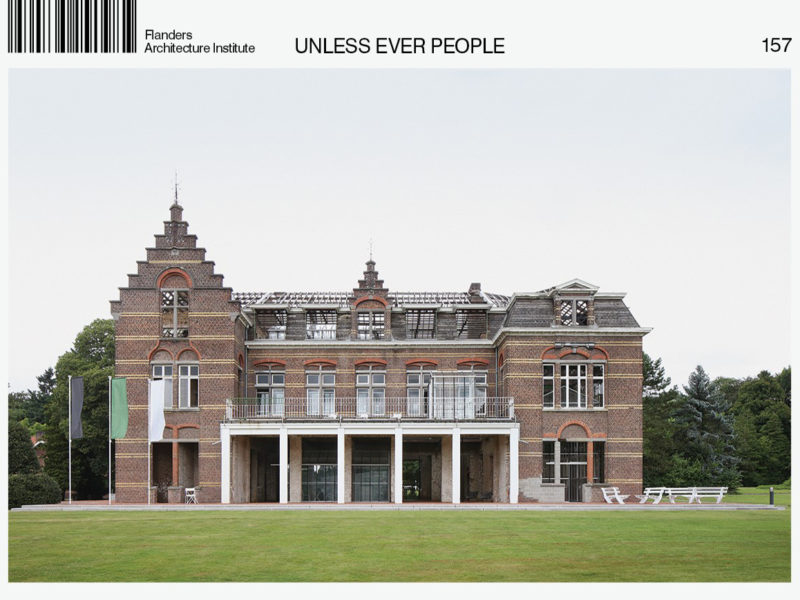

Image: de vylder vinck taillieu architects

KARUS is a network of psychiatric hospitals, day-treatment centres, housing projects and mobile services in the region of Ghent (Flanders, Belgium). Since 2014 there has been an ongoing project titled ‘The psychiatric centre of the future’. This ever-evolving thought experiment has resulted in several infrastructural implementation projects, most importantly the ‘Kan. Triest Plein’, ('Canon Triest Square'), and the renovated heritage building ‘Dageraad’ (‘Dawn’) for the treatment of people with a psychotic vulnerability.

Both projects were achieved through a remarkable process of co-authorship between architects, philosophers, board and staff members, managers, doctors, patients and visitors. The co-production was an extraordinary experience, although not an easy one, and sometimes even uncomfortable and confusing, but precisely because of this, deepening and meaningful.

The struggle forced me, as general director, to tackle the complicated relation between architect and commissioner. In the case of the psychiatric centre, this relation has many layers, and collaborating actors are not always aware of the barriers that exist to the realization of a true co-production. Below I describe five lessons to understand what this struggle was about.

1. Connected by an Abyss of Mutual Misunderstanding

Commissioner and architect use the same words: ‘space’, ‘definition’, ‘possibilities’, ‘function’, ‘inside’, ‘outside’, ‘relation’, ‘use’, etc. However, the substantive, conceptual and semantic coherence of these words is completely different for each of them. As a result, this led to a mutual feeling of misunderstanding and disconnection. The words we used as well as the paradigms we employed to look at the world — i.e. the spatial position of humankind in the world — were irreconcilable at first. The gravest danger was to attribute this semantic abyss to personal issues or character traits and, in doing so, to compromise a mutual openness — ‘architects are strange people who always want to do special things’ — and vice versa — ‘the commissioner is a difficult man who always wants things to go his way’. Such ideas impede a constructive collaboration. They obstruct the exploration of co-creative zones and the understanding of each other’s paradigms.

The acknowledgement of our mutual misunderstanding offered a way out. It was an acknowledgement of the ‘blindness to blindness’. All parties journeyed together through the abyss that connected us. One of the main goals was the repurposing of a half-demolished heritage building. We started out with a heterogeneous group led by architect-philosopher Gideon Boie and his collaborator Fie Vandamme, who gathered directors, architects, patients, visitors, board and staff members as well as managers to reflect on the meaning of the ‘quality of space’ in the ‘psychiatric centre of the future’. Whatever the various meanings might have been, all ideas were considered equal and were taken seriously. We joined together in an effort to make ‘sense of non-sense’. This way, we met each other as anthropologists, who became submerged in other cultures and in doing so learned each other’s native tongues. Although commissioner and architect may collaborate on a singular vision, the patient population varies. They return home or to work, new patients arrive and are confronted with the danger was to attribute this semantic abyss to personal issues or character traits and, in doing so, to compromise a mutual openness — ‘architects are strange people who always want to do special things’ — and vice versa — ‘the commissioner is a difficult man who always wants things to go his way’. Such ideas impede a constructive collaboration. They obstruct the exploration of co-creative zones and the understanding of each other’s paradigms.

The acknowledgement of our mutual misunderstanding offered a way out. It was an acknowledgement of the ‘blindness to blindness’. All parties journeyed together through the abyss that connected us. One of the main goals was the repurposing of a half-demolished heritage building. We started out with a heterogeneous group led by architect-philosopher Gideon Boie and his collaborator Fie Vandamme, who gathered directors, architects, patients, visitors, board and staff members as well as managers to reflect on the meaning of the ‘quality of space’ in the ‘psychiatric centre of the future’. Whatever the various meanings might have been, all ideas were considered equal and were taken seriously. We joined together in an effort to make ‘sense of non-sense’. This way, we met each other as anthropologists, who became submerged in other cultures and in doing so learned each other’s native tongues. Although commissioner and architect may collaborate on a singular vision, the patient population varies. They return home or to work, new patients arrive and are confronted with the empty, half-demolished building, and come to their own conclusions. In short, we cannot think each other’s thoughts, yet architect and commissioner need to arrive at a shared synthesis, condensed in bricks, spaces and spatial relations, while continuously accounting for the position of changing patients, visitors and staff members.

2. The Co-Creative Relation Between Client and Contractor

The ‘usual perspective’ regards the collaboration between commissioner and architect as a temporary relation between client and contractor. Even the European regulations for the appointment of an architect employ these concepts in defining the roles and underlying relations. The commissioner chooses a suit- able architect through a tendering process, someone who can translate the programme requirements into square metres, spatial relations, walls, doors, etc. This is valid when it concerns the construction of straightforward utility buildings. The more these definitions and functions are fixed, the more the architect merely needs to prepare a technical scenario. But the complex architecture in the world of psychiatry demands a different set of relations. And by ‘complex’ we do not mean this in the sense of structurally and technically complex, but rather the complexity of meaningful social lives that find their place within the physical space. It is about the treat- ment and care of people who, in light of their psychosocial problems, are going through a vulnerable phase in their lives and are surrounded by therapists and staff members, and receive visits of family and friends in a hospital context.

The more a building becomes a complex space within which social life unfolds, the greater the interdependency of architect, commissioner and user. Such a project demands vision, inspiration and creativity, but needs most of all a different definition of the collaboration between commissioner and architect. The client-contractor relation becomes untenable here. It is more about a co-creative process where ideas, concepts and the development of a vision condensate in spaces that are part of a specific context of users. In the encounter with physical space, the user becomes a co-author of the meaning of the spatial concept. Here, more than ever, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. In the end, users decide whether spaces are valid or not. We will return to this later, but let us conclude here that the road to an added spatial value demands the exploration of the user’s perspective. The experience of the user mercilessly pierces through the narcissism that unwittingly creeps into the collaboration of the commissioner-architect duo.

3. The Entanglement of Developing a Vision on Care and Space

At the start of the development of a vision, I was urged to first think about a consistent and coherent vision on care, and to only approach an architect afterwards. The development of a complex architectural concept is usually regarded as the result of a linear, algorithmic, sequential process. Once the commissioner has a clear vision on care, it can be translated into programme requirements for a number of rooms, meeting rooms, supervisory rooms, toilets, storage rooms, studios, etc. The skilled architect subsequently transforms the programme into an optimal, feasible and affordable design. The trouble with this classic Fordist paradigm is the division between thinking and doing. The com- missioner is responsible for the abstract reflection and the architect assembles the various parts into a coherent whole. This linear method does not allow for feedback and as such results in a project with no sense, or rather ‘non-sense’.

Meaning is not produced in a linear process, but in a recursive process. In thinking about physical space, we considered the relations, situations and organization of our vision on care, which was subsequently retranslated into the relations, coherence and organization of physical space, and so on. We learned that space cannot be considered separately from what may, will, can or should happen within it, and vice versa. The multiple layers of a process of producing meaning is what is known in system theory as a ‘recursive process’. Space, function and use interre- late in a circular way, and thinking about one aspect implies a spiral-like progress of thinking about the other layers. The process can only deepen if there is a far-reaching and long-term collaborative relation between commissioner and architect, and if both accept that the user is the ultimate test for what can be considered a qualitative space.

4. The Material Environment is Not, but is Constantly Becoming

Reality, wrote Heraclitus of Ephesus, is an ever-living fire and a movement of opposites attracting and repulsing each other. As a result of this dynamic, the multiplicity of things comes into being. An architectural concept should be open to this eternal flow of change, the panta rhei. Usually, attention is focused on the ‘being’ of a building and its use, but we forget the ‘becoming’, the potential, the not-yet-achieved, not- yet-imagined. The central idea of a continuous change is diametrically opposed to the rigid principle of inertia. Indeed, inertia confirms the way something is as it is and focuses on its preservation. The Heraclitean approach instead emphasizes co-evolution. It is crucial to allow changes in target audience, needs and expectations. The tension between what an architectural project is and, influenced by a changing context, what it should be and should become provides the necessary adaptive energy. Evolving with the environment gives rise to a continuous process of change and renewal.

A relevant architecture not only con- forms to the existing order and habits, but is able to evolve with the new situations it has itself created. Today’s architecture should define the conditions of tomorrow, to allow for an adaptive and innovative process. It is an operational learning curve through action and use. Concepts and insights should remain sufficiently flexible so as to make sure they are not already outdated by tomorrow. The social and spatial organization of a psychiatric centre is an endless chain of transformations with subsequent cycles of creation, destruction, innovation and reconstruction. Here we emphasize the ‘optional value’ and we tolerate ‘low-cost failures’. The focus is not only on the advantages of what exists, but also on investing in what could be, what could become. More specifically, we witnessed how an outdated heritage building was transformed through its new defini- tion, renovation and use. The fact that the Kan. Triest Plein already needs reconceptualizing in its short lifespan proves this even more.

5. A Space of Possibilities Presupposes a Calibration of its Definition in Relation to its Use

In the design of the Kan. Triest Plein we started from the assumption that minimizing the definition of use would result in an inversely proportional space of possibilities. Patients, visitors and collaborators would appropriate, colonize and co-create the scenic monument. We tempered our spontaneous tendency to direct how the spaces could or should be understood. With the exception of several greenhouses and a few tables and chairs, the spaces are physically open and free, with minimal infrastructure for use. If everything went according to plan, users would create the spaces they needed in the moment. Contrary to our expectations, we observed that this minimal definition did not automatically lead to a proportional creative use by patients and collaborators. I will now walk the reader through a few hypotheses.

We might define three groups of users. The first consists of youngsters. They use the space according to their own understanding and desires. They use the infrastructure as a place to meet, to gather in hidden corners, do karaoke in the mini-theatre or talk near the open fireplace. They loiter, smoke, listen to music. The second group consists of adult patients and visitors. They approach the space with a certain awkwardness or shyness. They mostly stay on the fringes, on the threshold between inside and outside, alone or together. The space offers the possibility to sit outside, with the building as a shelter in the open field of grass. A third group ignores or rejects the building. They walk around it. They do not know what to make of the ruin and wonder when the roof will be built. A house without a roof is ‘unthinkable’ and therefore ‘unusable’. They do not like it.

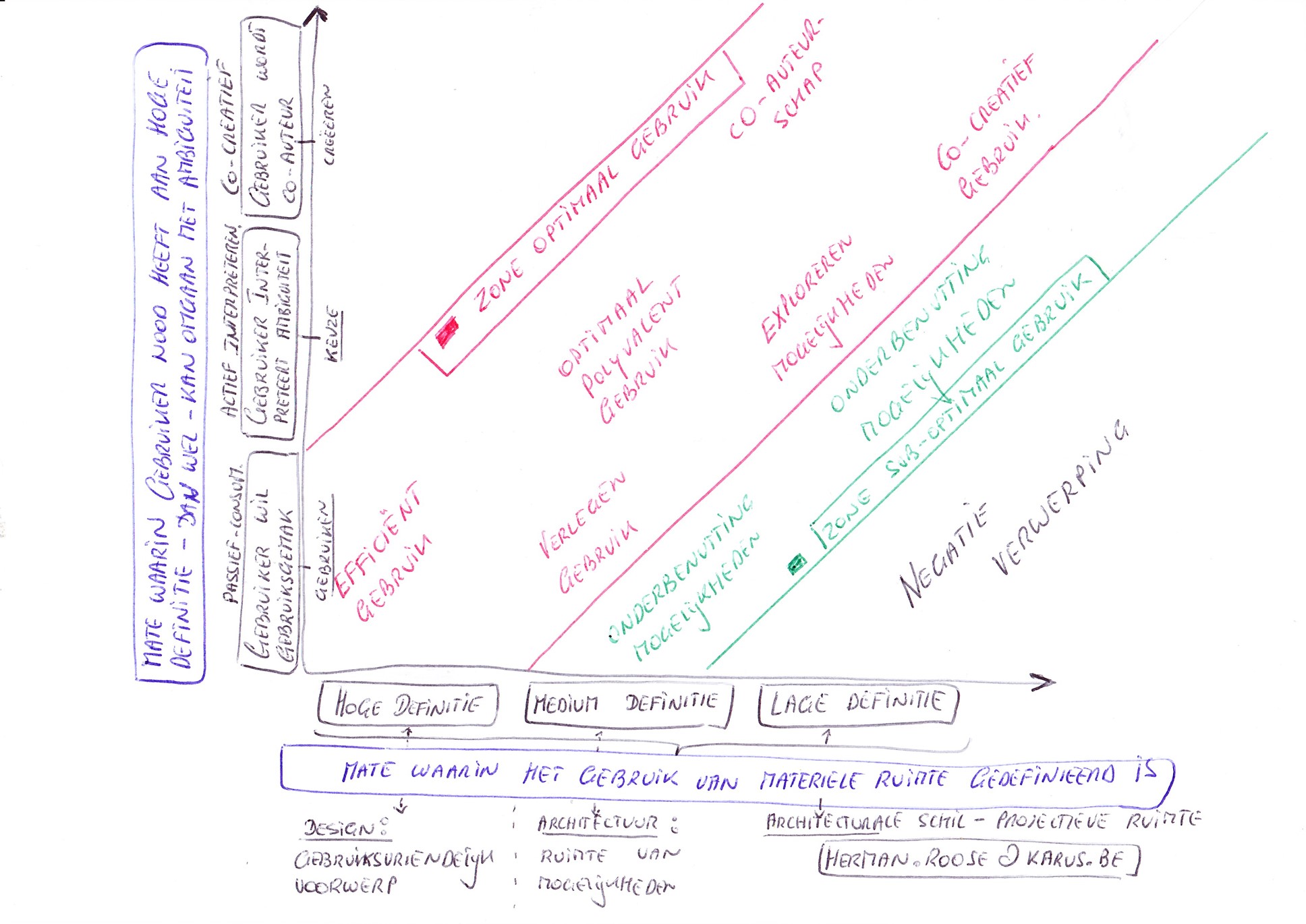

If we think this through, we arrive at two dimensions which should be considered in relation to each other.

Dimension 1: the measure of defining the material environment

To account for the demands of a given situation or context of use, the designer will position themselves somewhere on a continuum between, on the one hand, a strictly defined design (‘user-friendly’ and even ‘determined’), and, on the other, an undefined design (an ‘open space’). In the case of a high definition, there is little variation of use possible. The finality of the object of use gives rise to little or no misunderstanding. The design makes for an efficient and effective use, and there is no ambiguity. The user is passive, receptive, consuming. The limit follows a poka-yoke principle and makes wrongful use impossible. Variation and interpretation are not taken into account. A traditional hospital complex or a ‘bed house’ belongs in this category. Here we can hardly talk about architecture, at most about user-friendly and functional design.

In the case of a medium definition, there is room for polyvalence, variation and interpretation. The user is no longer a passive consumer but can contribute to the definition of the space and create their own added value on-site and in real time. The space can be used in various ways and is indifferent towards its use for meetings, parties, encounters or education. The renovated building of Dageraad, which today houses people with a psychotic vulnerability, is an example of this medium definition. Here, an architectural understanding provides most of the added value (or rather, does not destroy any value as non-sense architecture). The low definition is at the other end of the continuum. It is about a minimally defined space where the user can experiment and appropriate at will. The user fully becomes a co-author of the space in relation to their own contextual needs and requirements. The Kan. Triest Plein belongs in this category. Here, architecture recedes and creates a shell, a projective space which can be filled in freely.

Dimension 2: the extent to which the user can deal with the ambiguity of the material environment

Not every human being can deal with an equal amount of ambiguity in their encounter with physical space. For a number of patients, the acute hospital- ization in a psychiatric centre means a fundamental disruption on various levels. Many need something to hold onto at that moment, something familiar. This also applies to space. Patients who experience such disruption cannot handle extra spatial ambiguity. Things need to be recognizable, accessible, friendly. A different group of patients or visitors likes the possibility of appropriation, and they manage to handle a certain amount of spatial ambiguity. We have noticed that most youngsters belong to this group. They use the medium-defined spaces and objects at will, which are building blocks to arrange the space and life itself. Patients and staff who feel at ease with a high measure of material ambiguity and are able to appropriate this to their own needs are rather rare. Either way, there is an inverse relation to the extent to which patients can deal with ambiguity and the extent to which the spatial environment needs to be defined.

The optimal use situates itself in a match between these two dimensions. We can schematize this as follows:

Bibliographic note: Herman Roose, “Design Dialogue and Co-Autorship: a Social-Constructionist Approach”, in Unless Ever People, de vylder vinck taillieu and Gideon Boie (BAVO), eds. (Antwerp: Flemish Architecture Institute, 2018), 228-237.

—

The book ‘Unless Ever People’ is published by the Flemish Architecture Institute in 2018 on the occasion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition of Venice, curated by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. who invited architects De Vylder Vinck Taiilieu and BAVO to present ‘Unless Ever People – Caritas for Freespace’ in the central exhibition.

—

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article