Article

Content without architecture

Gideon Boie

4/3/2024, A+

Image: David Ducon

Architecture for culture is often about everything but culture. Take the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, designed by Frank O. Gehry. The urban importance of the building exceeds the intrinsic value of the exhibition space many times over. The museum is the crown jewel in the revitalization of the riverfront and, by extension, the entire city. There is also little chance that your city trip to Bilbao happened for the purpose of Guggenheim's collection. The urban function of a palace of culture is as old as mankind. Consider the Parthenon, which was most likely an empty building in its own right, and cultural center Westrand in Dilbeek, designed by Alfons Hoppenbrouwers, which was part of a Flemish policy for presence in suburbia.

Could it be that culture is only able to express itself fully when there is no building that draws all the attention to itself? Let’s perform a reverse operation and start at Cinemaximiliaan, a cultural initiative in Brussels that has been led by Annabelle Van Nieuwenhuyse since 2021. Cinemaximiliaan began in 2015 as an activity in the tent camp in Maximilian Park near Brussels North Station. The park at the foot of the WTC, where no less than a thousand refugees stayed, became a symbol of the refugee crisis that shook Belgium. Every morning there were long queues in front of the Immigration Office, which was then located in the pedestal of the vacant WTC.

A spontaneous self-management developed in the tent camp. Refugees and volunteers organized a kitchen, sanitary facilities, crèches, a school, and so on. Lieven De Cauter called the camp an infra-architecture. The organizational form came close to zero slope, but all the more necessary for that reason. The tent camp stood in immense contrast to the hyper-architecture of the surrounding corporate buildings with their gleaming glass facades and empty office floors. In that context, a group of volunteers organized an open-air cinema. Gwendolyn Lootens and Gawan Fagard took the initiative. The film literally brought light into the darkness, a moment of cultural exchange in a spatial context reduced to bare life.

After the camp was evacuated by the police in October 2015, the cinema took on a life of its own. During “home screenings,” volunteers opened up their living rooms for a movie night with undocumented migrants. Film screenings were also organized in asylum centers across the country. The movie screening was a pretext to cook together, exchange experiences, meet people, play music and whatnot. Later, in 2017, the cinema took up residence in rue Manchester, which has since become home to other cultural organizations such as Recyclart, Decoratelier and Charleroi Danse. It allowed Cinemaximiliaan to expand its operation to include performances, exhibitions and film productions.

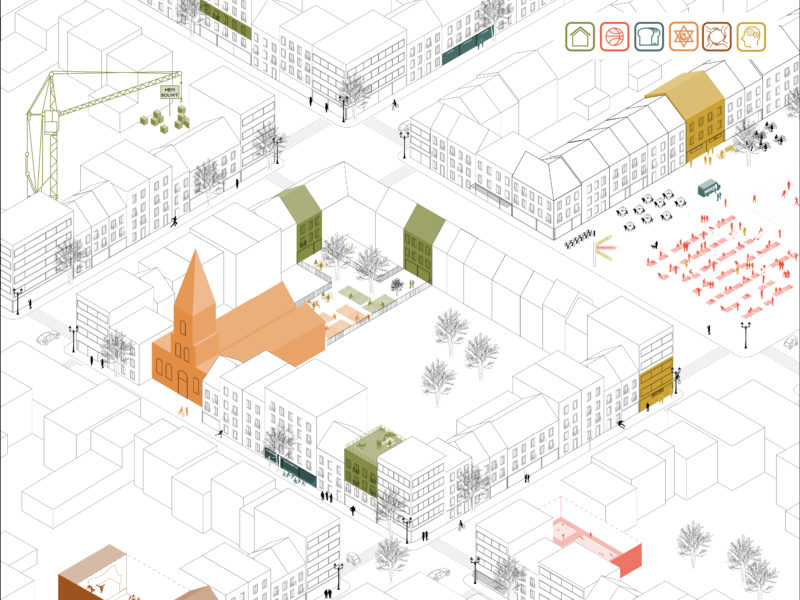

The permanent accommodation does not take away from the fact that Cinemaximiliaan is primarily about situationist architecture, even within its structural operation. The festival Cinema Trottoir (2022) transformed a mundane street into a cultural scene. A simple building scaffold served as an auditorium, the street facade as a projection screen. The audience is given headphones and the projector is in the bedroom of the opposite neighbor at Cassonade, the restaurant without a price list. A similar dynamic can be seen in the open-air cinema of Park Albert, a summer festival on the central strip of Avenue Albert II at the initiative of LabNorth, 1010a+u and Omar Kashmiry+Maarten Weyns. The common thread remains the creation of security and mutual care in the cultural exchange with near strangers. A distant public space thus briefly takes on a more human face.

Remarkably, Cinemaximiliaan had plans to design its own residence in 2020. In addition to some obvious functions, the residence was to include a guest house. The project was made possible through the pooling of philanthropy and public grants. Office KGDVS surprisingly acted as architects for the charity, but the project remained up in the air. Was it a little bit too much substance for architecture? The question is whether Cinemaximiliaan’s situationism needed a grand architectural gesture at all. The project is still in the pipeline for so many years later. Today Omar Kashmiry (Zin-Architects) works as an “architecture representative” within the non-profit organization, which suits the nature of the organization better.

There are several examples of such spontaneous additions to the cultural infrastructure of Brussels today. Recyclart, an organization that emerged in 2010 within the vacant station Kappellekerk in Brussels, is one such example. In addition to cultural events, parties and lectures, Recyclart organized a social kitchen and ditto workshop. Another example is Openstreets, organized by Filter Café Filtré. Streets are opened up during the summer as a platform for dance performances, cooking workshops and whatnot. The architecture of these and other cultural initiatives is less eye-catching, but at least equally decisive for the city’s identity.

Lieven De Cauter described Cinemaximiliaan as a “heterotopic laboratory” for a “new global culture of the Anthropocene. Transmigrants and undocumented persons are absorbed in another place, where cultural exchange, caring support and commoning of often traumatic experiences become possible. At the same time, one can describe Cinemaximiliaan temporary situations as a heterochrony. Michel Foucault used this term to refer to museums and libraries as an infinite accumulation of time. The festival equally constitutes another time in the urban experience, it is the spontaneous initiative that breaks with the daily routine and status quo.

—

Image: David Ducon

Draft translation of the article published in the A+ issue (Dutch and French edition) on ‘Building for culture’: Gideon Boie, ‘Inhoud zonder architectuur ’, A+ Architecture in Belgium, 306 (maart – mei 2024), 37-39.

—

Tags: Activism, Brussels, English

Categories: Urban planning

Type: Article