Article

An Architectural Future for a Mining Past

Gideon Boie

2011, AA Publications

Image: Stijn Bollaert

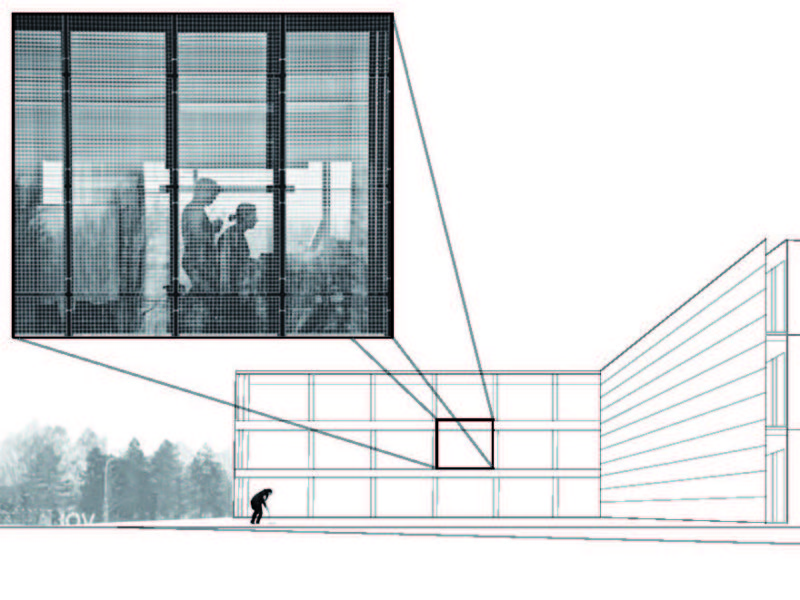

The Energy Buildings on the site of the former coal mine at Winterslag (Genk, Belgium) offer a platform for a programme of contemporary creativity, including a cultural centre, an exhibition area, design centre and reception room. The design by 51N4E links these creative developments to the community’s mining history, providing a clear and precise response to the question of how to deal with industrial heritage, the creative economy and urban redevelopment.

The Energy Buildings – specifically the machine hall and adjoining ‘barenzaal’ – are subjected to full-scale redevelopment without detracting from the many layers of historical meaning that envelop them. In this way, the design goes beyond the usual competing claims made for the conservation of monuments on the one hand and their development on the other. The main victim in such cases is the built heritage itself. In the first instance it languishes like a living corpse, in the second like an empty shell.

The architects refer to a light renovation based on voluntary limits and extreme directness. Consequently, the design does not seek a confrontation between old and new; nor does it overemphasise the relationship with the past. Rather, it preserves the industrial infrastructure, both movable and immovable, in the condition in which it was found. New additions are carefully incorporated into the natural identity of the mining site. At times this means that the interventions become almost indiscernible, as is the case with the whitewashed internal walls and the extra perforations in walls and floors.

The main additions are the two large, aluminium-coloured theatre blocks. Contrary to the prescriptions of the masterplan, these are located in the angles of the T-shaped building, which makes them look like a natural accretion on the complex – one that slightly enlarges its characteristic compactness. These two alien elements are further integrated into the historic complex by enveloping them in a concrete wall coloured an appropriate brown. Added to this are some surreal touches, such as the ceramic-tiled floor that runs from the interior to the exterior and forms a walking route with a view of the building and the surrounding site.

The communal history of mining is a central focus in the redevelopment of the coal-mine under the direction of Genk town council, which bought all the land from a private equity company, Limburgse Reconversie Maatschappij. The closure of the mine in 1988 sparked a feverish search for a new purpose for the site. Public and private partners came and went and countless scenarios were developed, some more realistic and appropriate than others. The design of the Energy Buildings shows that well-considered development does not necessarily have to alienate the heritage from its past, but can in fact intensify the relationship. The footings for the industrial machines, for example, are used to create a labyrinthine plinth at ground level onto which the various parts of the programme can be attached. In the machine hall above, the turbines are displayed as silent witnesses to the past. By repeating the large, open space of the machine hall, the two theatre spaces and present themselves as the stage for the new creative production at C-mine.

The Energy Buildings are designed to function as a collective container for various creative activities. Each part of the programme is provided with a place in the labyrinthine complex, but no single part dominates. One barely senses, from one’s experience of the interior, that the cultural centre, with its two halls, occupies by far the greatest area. What is more, none of the parts of the programme has an individual facade that would enable it to attract the visitor’s attention in its own right. The design of the entrance is similarly understated, as a light structure in black-painted steel. Given the fluid, unpredictable nature of creative work, and the difficulty of compartmentalising such activity, 51N4E have ensured that each space remains open to the needs and wishes of the moment. In this context, it is understandable that the various spaces are not even given a name on the basis of their normal function, whether theatre, exhibition space, meeting rooms or restaurant/café.

The project concentrates solely on the design of the container in which various creative activities can be pursued without constraint. This explains the unusual theatre, a single large open space, with no division between stage floor and seating, which sets up new relationships with the audience. New relations to the outside world are also established via an ingenious system of solar blinds that adjusts the incoming daylight. In the more enclosed, smaller theatre, there is no fixed stage or seating, which makes the space suitable for standing activities too. Here, the surrounding balcony enables the room to be experienced in several ways. The exhibition area, in turn, has pivoted walls so it can be divided into four parts in no time.

Lastly, the historic machine hall plays its part as the linking element in the total creative experience, acting as a shared vestibule for the various programmes. The architects refer to it as a kind of expansion chamber that regulates the flow of people between the private, internal parts of the programme and the public forecourt. They also mention traditional law courts, where oversized corridors, salles de pas perdus, provide a suitable space for anonymous and informal interaction. The connecting space of the machine hall goes beyond pure necessity or function, forming a many-branched, monumental mediating space that invites visitors to stroll through the building and enjoy the creative activity around them. More than this, it stimulates their own sense of creativity – in line with a guiding principle of creative towns and cities ‘seeing enterprise leads to enterprise’.

The decision to transform the Winterslag mine site into infrastructure for creative industries now seems entirely natural. But it was preceded by years spent looking for a solution, which saw countless scenarios appear and then vanish due to lack of support. In the interim the mine site languished, a cheerless witness to a glorious past. The completion of the Energy Buildings enables C-mine to function once again as the place where Genk’s common wealth is produced and presented. And above all as the place where community life can flourish as it did before.

More specifically, the design for the Energy Buildings is the lever by which Genk can achieve its ambition of growing into a town with several hubs. In traditional towns and cities, outlying boroughs often come off worst in terms of attention and investment. Genk is reversing this logic by equipping the old mining sites as fully fledged urban centres, each with its own specialisation. While Winterslag is being developed into the creative heart of Genk, Waterschei is being marketed as a science centre and Zwartberg as an industrial park. As part of this scenario, the town’s main square, the Stadsplein, is being developed as Genk’s commercial heart. The municipal authorities are pursuing a vision of the town as a socio-artistic factory. Welfare and prosperity are no longer created solely within the walls of the traditional factory. Nowadays, the entirety of urban activities is a dynamic source of wealth.

Text published in: 51N4E, Double or Nothing, AA publications, London 2011.

Tags: English

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article