Article

Everybody Architect, a note on the authorship of the square

Gideon Boie

25/05/2018, Flanders Architecture Institute

The belief that ‘Everything is architecture’ recurs at different moments in architectural history. I remember the ‘helmet of Hollein’ as a fundamental lesson by Lieven De Cauter in an article on the expanded field of architecture. It has become a commonplace by now. Recently our dear compatriots at Office KGDVS claimed ‘Everything Architecture’ as the title for a retrospective exhibition of their oeuvre. It puzzled me, because how can you claim that everything is architecture while placing it under one name? How can we deal with this paradox? How can we ensure that the expanding field of architecture also allows for other architectural subjectivities? The ‘Kan. Triest Plein’ (‘Canon Triest Square’) offers a line of flight.

In the Caritas project, we always started from the premise that everything is architecture. In mental healthcare everything is part of the therapeutic setting, from the location (the asylum tucked away from the city) to the building typology (the pavilions scattered across the green) via the different elements of architecture (walls, doors, balconies, etc.), the materials used (brick walls can tumble upon you) and the interior design (from washable chairs to the different shades of white on the wall). Logically this absolute character of architecture in the psychiatric centre forced us to make architecture a topic of universal concern. Architecture is not just a technical affair to be discussed in a boardroom, but neither is it an aesthetic issue in the hands of someone’s higher sense at the design table. We created an architecture culture as an equal playing field that reached out to all, giving everybody the possibility to engage in the design dialogue regarding the psychiatric centre of the future.

The book you hold in your hands testifies to the joy and pleasure that were released in the moment of aesthetic emancipation. The brief was expanded, impossible desires demanded, the unexpected realized, so many dreams unleashed — we will not repeat ourselves here. Allow me to shortly note how the classic choreography of architectural production accordingly melted into thin air, giving way to emergent architectural subjectivities.

Again, here is a preliminary list:

The user-architects: the work groups made up of psychiatrists, managers, staff and patients were brought together around the design table to imagine the spatial qualities necessary in the psychiatric centre. Their knowledge provided the building stones for the psychiatric centre of the future. As the ‘user-architects’ took their role more than seriously, we saw how they became the ‘user-principals’ of the Kan. Triest Plein, even inspiring a patient to claim ‘Jozef is ours’ in a discussion with psychiatrists, therapists, managers and board members.

The ignorant-architects: from the start BAVO refrained from putting forward design directives, hoping to arrive at a design intelligence stemming from the psychiatric community itself. In a private chat at the office, the general director once laughingly called us the ‘little “Bouwmeesters” [“Master Builders”] of Caritas’. Later architecten de vylder vinck taillieu presented us as ‘project-director’, although ‘architect-curator’ would have been better as we directed little.

The joyful-architects: the proposal by architecten de vylder vinck taillieu to keep the building as-found was crucial to what we now know as the Kan. Triest Plein. Part of the magic creativity of the joyful-architects is their openness to work through the design with psychiatrists, managers, staff, patients and contractors. Everybody was welcome to suggest any inspiration they had and to contribute to the resulting gay architecture.

The principal-architects: the management and technical staff became co-producers of the spatial setting, allowing recursions in the architectural production process, making it as vital as life. They also cracked the algorithms provided by the joyful-architect by adopting them. At the Kan. Triest Plein, the management suggested switching the wooden floor planks one by one, by analogy with the concrete blocks that heal the brick walls. Likewise, the renovation of ‘Lente’ (‘Spring’) was shaped by the staff, overtaking the usual role of the architect-architect.

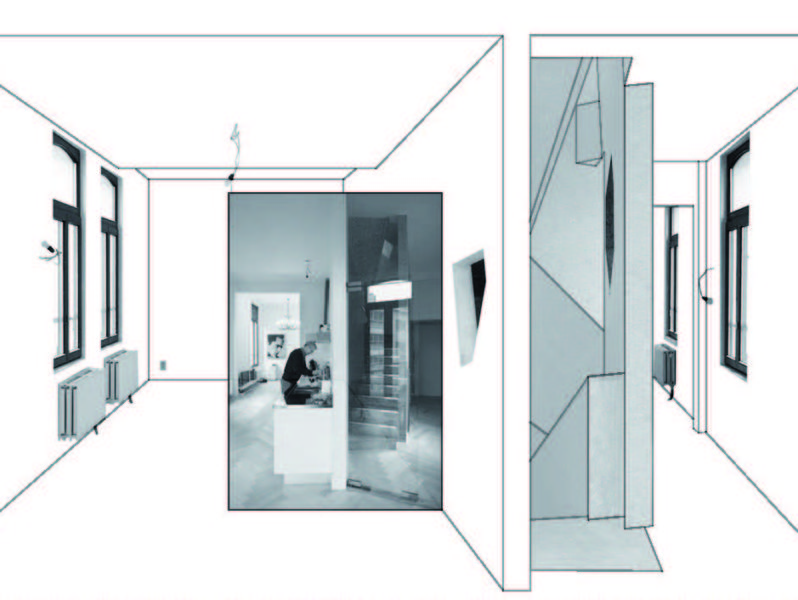

The architects-beyond-architects: this is the story of the team of ‘Dageraad’ (‘Dawn’), the Department for Psychosis Care, taking fate into their own hands and turning a vacant historical building into a space that truly fits the vision and service they wanted to provide. How these people cancelled out the usual role of the architect-architect is perhaps the ultimate stage of aesthetic emancipation.

The post-production-architects: people passing by the Kan. Triest Plein – patients, staff, students and visitors alike – appropriate the space, giving it a function and meaning according to their own needs and desires. They don’t care about the intentions or concepts, often they don’t even know the prehistory of the construction, and perhaps luckily so. Certainly, they take care of the building, if only by spreading the idea of the building.

The becoming-architects: the team of ‘Branding’ (‘Breaking Wave’), the Department for Forensic Child and Youth Psychiatry, learned a lot from what happened with Jozef and Dageraad and is gearing up for their building programme. And so is the team of ‘Kaap’ (‘Cape’), the Department for Child and Youth Psychiatry. Not to forget the team at the Department for Anxiety and Mood Disorders eager to move into Jericho, another heritage building awaiting renovation.

The arch-architects: the thing we know as the Kan. Triest Plein is a tribute to the founding architects of the psychiatric centre. Once upon a time, Kanunnik Petrus Jozef Triest (Canon Peter Joseph Triest) was working side by side with Monsignor Eugène Van Rechem, called by some the real ‘Bouwmeester of Caritas’ (‘Master Builder of Caritas’). Later came De Vloed Architects, leaving a considerable mark on the development of the psychiatric centre, all in accordance with the norms and values of the time.

All these actors together form the collective subject of the Kan. Triest Plein and force us to redefine the classic choreography of architectural production. The architect is defined in a law of 1939 as the guarantor of the fragile balance between commissioner and contractor, while keeping an eye on the public good. Media formats are fitted to this choreography, ensuring that the semblance of the architect-architect will stay with us for a little while, but our comfort is the spirit of the creative commons. Everybody is allowed to claim authorship of Kan. Triest Plein, but only if you leave equal authorship rights to others, join the collective subjectivity, and take care of the building accordingly.

Chapter from the book: architecten De Vylder Vinck Taillieu and BAVO (eds.), Unless Ever People, (Antwerp: Flemish Architecture Institute, 2018), 338-341.

ISBN: 9789492567079

Tags: Care, English, Psychiatry

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article