Article

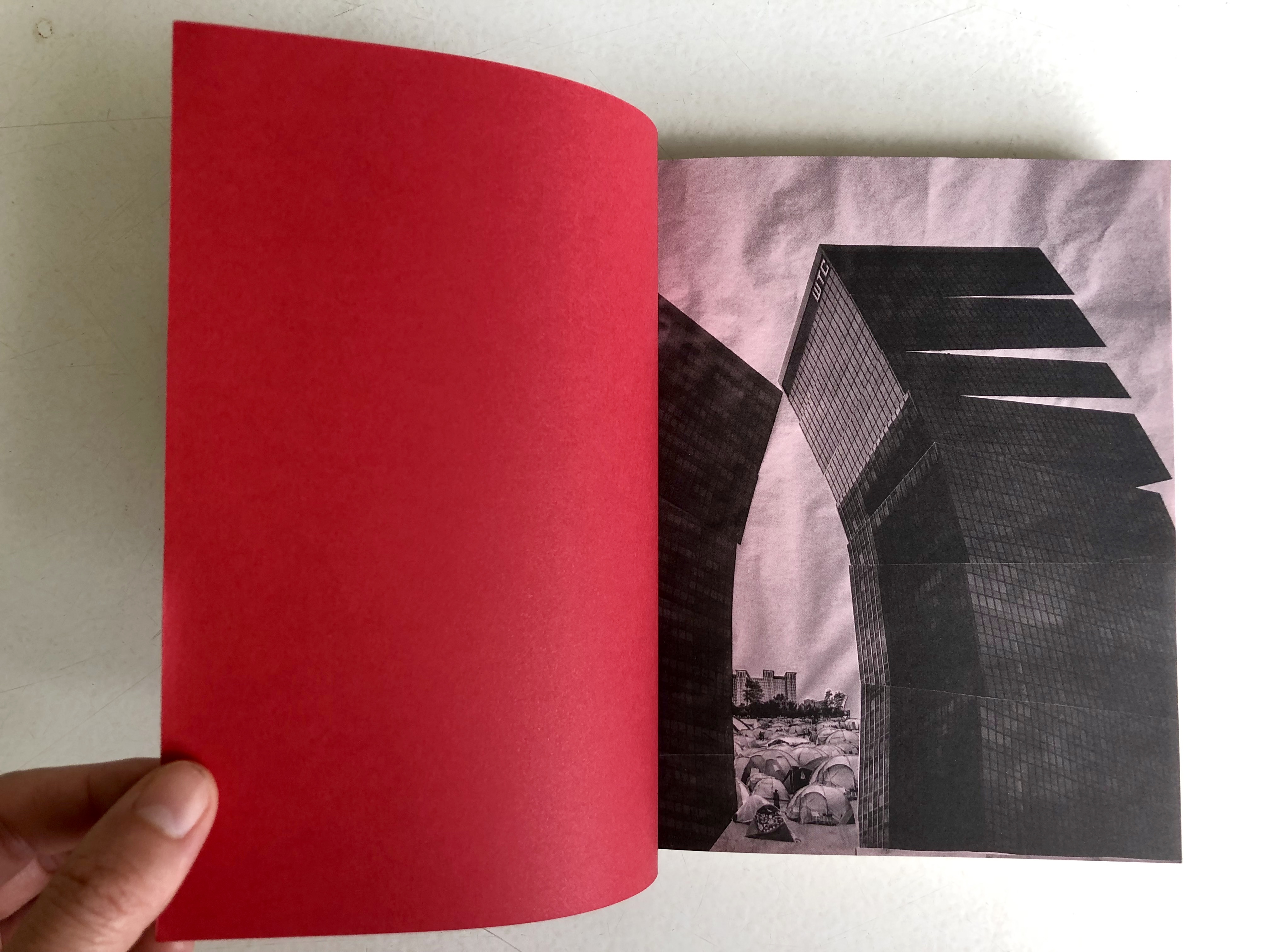

The WTC paradox

Gideon Boie

28/06/2019, KU Leuven

The temporary use of the WTC will expire in December 2018. The technical installations have been switched off, and the floors are once more empty. This also brings to a close the remarkable housing of artists, architects and students in a building that symbolises the urbicide of the North Quarter like no other. The KU Leuven Faculty of Architecture, Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels, may also begin the hunt for a new location. So, it’s high time to take stock of WTC 24. The question is whether establishing a faculty at WTC 24 meant anything for the major changes underway in the North Quarter? And what is the significance of WTC 24 for the future of architectural studies in Brussels?1

From Meurop

The story begins with a deluge of complaints over the years about the current location in the ‘Meurop’ Building on Paleizenstraat in Schaerbeek. Coussee & Goris renovated the former furniture shop in 1996 according to their in-house philosophy ‘structural work is finishing work’ (ruwbouw is afbouw). Despite the building’s robust design, it’s hard to conceal its defects in terms of the airflow, moisture, acoustics and general usage. Thus far, all the talk about renovations and overhauls (including installing palm trees bent over a scale model of the TOP Office) has done nothing to change the sadness. The goal to breathe new life into the building by transforming ‘Campus Brussels’ into a special project school — with its own place in the middle of Campus Ghent and Campus Heverlee — continues to muddle along.

The building presents itself as a ‘Palestinian refugee camp’, according to Lieven De Cauter. Beyond the aesthetics, the comparison also applies if we examine the internal social dynamics and the public relations in force. The spatial infrastructure of Meurop is at odds with the teachings of a school that has self-curated learning pathways and new learning methods. The school’s relationship with the neighbourhood is well below the freezing point. After the attacks of March 2016, a badge system was installed in order to keep out all uninvited guests. It’s safer to assign design tasks to students in Casablanca than to speak to a neighbourhood Moroccan resident. The food from the caterer is more affordable than the area’s eateries. Many students rent a room in Leuven just to commute every day to Brussels…

… to the WTC

Against the background of a moribund Meurop Building, the temporary use of the vacant WTC was a godsend. During the 2017-2018 academic year, Leuven’s Faculty of Architecture moved into the 24th floor of WTC 1. The annex to Leuven’s Faculty of Architecture was quickly nicknamed ‘WTC 24’. An artists collective on the 25th floor functioned as an example of this new annex. Building owner Befimmo created ‘Up4North’: a cultural association that operates as a social lubricant for its largest developments and as a go-between for negotiations with creative actors. Up4North is a collaboration with architectural practices 51N4E and AWB (Architectural Workroom Brussels), who took up residence on the 16th floor. On the 15th floor, the joint venture of Jaspers-Eyers and 51N4E worked on the tender to give WTC towers 1 & 2 a new lease on life as office space for the Flemish Government. Throughout the year, all manner of creative professions were established on the 26th floor. The doors were thrown wide open for the IABR exhibition on the 23rd floor.

Whatever owner Befimmo’s foggy reasons for unlatching the doors, the stay at the WTC was an enriching, unforgettable experience for all involved. The paradox is that the spatial infrastructure of WTC 24 was perhaps even more tired and tatty than that of the Meurop Building; the air quality was much worse, the acoustics even lousier, the quarrel about space nearly got out of hand, the washing-up was always left for some poor dupe and yet … everyone remained unanimously positive. A few factors explain the success of the space:

- THE ‘WALK-OUT’: leaving Paleizenstraat was a pleasurable, if minor, transgression. Likewise, the pompous architecture of the WTC’s lobby. For the first crossing, each student carried a stool. The professor personally uncorked the wine bottles. An atmosphere of light anarchy dominated the entire academic year. The school environment was effectively ‘no school’ due to the lack of classrooms, signs, auditoriums and reception staff … It was never quite clear whether class would go through, a lecture was in session or if a reception was being held. Better yet: the receptions became the ideal moments for knowledge transfer.

- REAL WORLD PARTICIPATION: some design studios organised themselves as an ‘authentic’ design agency. Some of the students claimed a dedicated workplace. The education went far beyond the abstract study of the social drama unfolding in the North Quarter, it was right in the thick of it. There could not have been a better settling-in period. Moreover, the education became part of the reconquest of the North Quarter. The ambition of the Brussels Government Architect to break up the grand plans of the office market formed the perfect backdrop for the students’ education. Not to mention the background of the police actions that State Secretary Theo Francken ordered for Maximilian Park and the citizens courageous push back against this. Architectural studies were part of the social debate for a year and a half, or were at least never far from it.

- THE SCHOOL AS COMMONS: the gaping void of the office floors was hastily filled with a minimal school infrastructure. It entailed many tables on trestles, chairs, a kitchen unit, a printer, two projectors, a few lockers and toilets. More was not necessary. ‘Self-organisation’ became our slogan. There was no back office. Nobody could retreat into the institute. There was no secure ‘council chamber’ for teachers to discretely withdraw to. No closed studio or auditorium for training ‘obedient sheep’. The open floor symbolised the horizontal organisation of the education on offer. The school’s organisational form was the sum of all its activities. A small group of students spontaneously began to keep the school operating.

- THE VIEW ON BRUSSELS: the 360° panorama functioned as an attraction, certainly when organising open classes and public events. The commuting students got to know Brussels from a great height. It was much easier to invite guests up to the eagle’s nest of the WTC. An empty floor for education: it appealed to the imagination. The all-encompassing view did astonish visitors. The meaning of ‘Brusselisation” could be felt in each person’s body, could be explained by looking in any direction and it charged every design transaction with meaning. Going to school at WTC 24 became an element of pride rather than shame.

… and back?

The question now is what the future will bring. The tone appears to be set for a permanent nomadic existence of architecture schools in Brussels. A new temporary location, KANAL, has come into view, now with the French-speaking architecture schools in it. That is until the construction site erupts there as well. Or are we moving on to the base for WTC 3 and 4, where Befimmo is also preparing construction plans for a new tower? And what do we do with the vacant space at the CCN/North Station? Or the former cycle station under the arches of the North Station that has since been converted into retail space?

The temporary location of an architecture school should not only be viewed as a logistical issue, but as an opportunity to reconsider the place the school occupies within the city. From this perspective, it is significant that a group of students who held WTC 24 above water organised under the name ‘PILOT BXL’ and revisited the original thinking process around Meurop. A scale model was developed that utilised the spatial and pedagogical dynamics of WTC 24 to relaunch Meurop. A lecture series will provide the intellectual sustenance. A dinner in the library gave a preview of the future of the architecture school. A long march through the institution surely lies in waiting, but it’s a good sign that the Pilot BXL initiative has already been taken over by the POC (Permanent Education Committee).

The question remains as to how we can stay true to the experiences at WTC 24? Temporary use for an architecture school is not only a logistical issue, but is primarily about the place the school is afforded within the city. In that light, we must also dare to adopt a critical stance toward the success factors mentioned. Let us begin in reverse order:

There is little to criticise about the panoramic view of WTC 24, except that the beautiful background did not necessarily inspire a critical relationship between the educational buildings and the city. The temptation to get cosy high and dry in the eagle’s nest was very strong.

At WTC 24, the ‘school as commons’ was sometimes too confined to the organisation, such as the fight for square metres, respecting one another’s materials, noisy neighbours and that pervasive question ‘Who’ll do the dishes?’ Undoubtedly, these matters are crucial discussions in the ‘commoning’ process. At the same time, it does make one dream of a more substantive interaction between design studios.

Having an impact on the North Quarter will require more time than a school assignment. Students contributed to the festivities on the street and the rooftop terrace, but they never managed to interact with the mysterious 15th th floor where Jaspers-Eyers and 51N4E are discretely working on the future of the tower. The practice was so close yet so far away.

Lastly, WTC 24 was unable to shed its ‘school’ yoke. The difference between the service contract for AWB and 51N4E and the lease contract for the Faculty of Architecture is telling. It demonstrates that the education was viewed as a mere consumption of space and the school’s contribution to the future of the North Quarter was virtually nil.

The issue extends beyond WTC 24; it’s just as relevant for the future temporary housing at KANAL, a return to Meurop or anywhere else. The fundamental question is what place to assign the urban complexity of Brussels within architectural studies and vice versa. For now, the suspicion is growing that the Faculty of Architecture was mainly tolerated in Jaspers Town. Conversely, the educational institute already appears to be satisfied enough to grant credits to students.

Book chapter in ‘WTC Tower Teachings, reports from one and a half years of nomadic architecture education in Brussels’, published by KU Leuven Faculty of Architecture, Brussels, pp. . 92-96.

This is an elaborated version of a text published by the A+ magazine on 27.11.2018

Read the online version: https://issuu.com/faculteitarchitectuursintlucas/docs/wtc_tower_teachings

Categories: Architecture

Type: Article